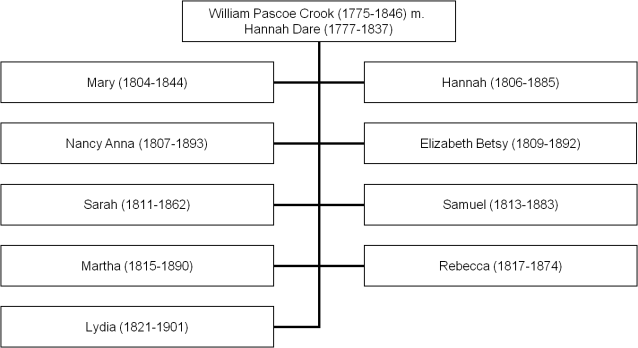

My favourite missionary family of late are the Crooks of Tahiti – William and Hannah plus their eight daughters and one son.

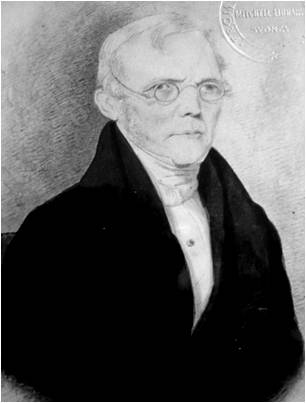

William Pascoe Crook (1775-1846), former gentleman’s servant and later tin-worker, arrived in the South Seas (i.e. the Pacific) in 1797 with the first fleet of missionaries dispatched by the London Missionary Society (a year earlier, in 1796).  He was dropped off at the Marquesas in June of that year, and, after the departure of his colleague John Harris, toiled there alone until the Butterworth ‘rescued’ him and returned him to England in May 1799.

He was dropped off at the Marquesas in June of that year, and, after the departure of his colleague John Harris, toiled there alone until the Butterworth ‘rescued’ him and returned him to England in May 1799.

Crook had had a rather distressing time during his year in the Marquesas. There ‘ever[y] temptation ha[d] been of such a strange sort’ that he wished to ‘blush and be confounded before the Lord.’ After a year of temptations, argues Alex Calder, ‘Crook long[ed] to reconstitute his identity in the confirming looks of someone who knows how to read him rightly’ – in other words, his desire to ‘blush and be confounded before the Lord’ was, among other things, a need to be reconstituted as a white, western man, a pious missionary, and a martyr to temptation, rather than its slave. Upon his return to England he worked on a dictionary of the Polynesian language, wrote up an account of his experiences, and married a respectable young Englishwoman: Hannah Dare (1777-1837).

* * * * * * * * *

William and Hannah sailed together for Tahiti in 1803, stopping off at Port Philip, and three weeks later, Sydney. ‘But painful intelligence awaited him there, for on his arrival in that city he found that the Society Islands were all at war, and that the missionaries had all left except two, Mr. Hayward and Mr. Nott.’ This was the ‘separation’, as it was known, and equated to the abandonment of the South Seas Mission in 1798 by eleven of its missionaries, supposedly spooked by a ‘plan to seize our women and property’, but probably as much to do with the difficulties, temptations and dangers of missionary work for a group of highly unprepared and idealistic young men (and a small handful of women).

‘But painful intelligence awaited him there, for on his arrival in that city he found that the Society Islands were all at war, and that the missionaries had all left except two, Mr. Hayward and Mr. Nott.’ This was the ‘separation’, as it was known, and equated to the abandonment of the South Seas Mission in 1798 by eleven of its missionaries, supposedly spooked by a ‘plan to seize our women and property’, but probably as much to do with the difficulties, temptations and dangers of missionary work for a group of highly unprepared and idealistic young men (and a small handful of women).

The Crooks settled in Sydney, William founding a school and for some time being the colony’s official chaplain, Hannah setting up a millinery business. But though at this time their ‘prospects in life were highly flattering… [they] could not be happy, but sold all off, and returned to the mission, considering that only to be [their] proper place.’

By now Tahiti was a very different place from the one abandoned by William’s colleagues in 1798.  Years of ‘civil war’ on the islands, between the ari’i (chiefs) and over the role of ari’i rahi (paramount chief), had been resolved with the victory in 1815 of Pomare II

Years of ‘civil war’ on the islands, between the ari’i (chiefs) and over the role of ari’i rahi (paramount chief), had been resolved with the victory in 1815 of Pomare II  who had, fortuitously for the missionaries, declared his intention to convert to Christianity in 1812, and was ultimately baptised in 1819.

who had, fortuitously for the missionaries, declared his intention to convert to Christianity in 1812, and was ultimately baptised in 1819.

William Crook had an illustrious missionary life, particularly in his close relationship with the Pomare family. My interest in the Crooks stems much more from their family circumstances – eight daughters and one son had been born by 1821. While the Crook children were often of great assistance to the mission – particularly the two elder daughters, Mary and Hannah Jr., by 1827 the Crooks were in a deep quandary about what to do for their family’s temporal and spiritual wellbeing.

‘What to do for our family we know not. It is a discouraging thing to think of. One or both of us the parents will soon be removed and our poor girls will be cast among semi-savages except they take refuge in some of the missionaries houses, and they have enough to do to take care of their own and in a short time will be in the same state as ourselves. We can form no virtuous connexions for our girls, nor can we put them into any situation where they may be useful to others. What to do for them we know not’ (1827).

The response of the London Missionary Society Directors to the Crook’s repeated pleas for guidance and assistance was less than helpful. After exhorting them to ‘cast this, as all other burdens, upon Him who has enjoined upon his peoples, not to be anxious about to-morrow, but to rest assured, if they are engaged in doing his will, he will take care of them and theirs’, they further suggested that ‘the families of the Missionaries should, if possible, become settlers in the Islands’(1828). To this idea Crook expressed his exasperation in no uncertain terms: ‘the experiment has been fully tried by three married men… Now if men who have traversed the ocean in every direction cannot succeed, how are such girls as ours to succeed as settlers… As to identifying themselves with the natives or making rope and canvas, there are things that cannot be mentioned here without exciting the most unpleasant feeling.’

‘To us, your idea of civilising the country is very pretty in theory, but utterly impracticable.’

In the end, the Crooks felt forced to abandon their mission – a rare and striking case in which missionaries put their family ahead of their vocation. They returned to Sydney in 1830, and continued their religious and philanthropic work until their respective deaths in 1837 and 1846.

* * * * * * *

There are almost too many things of interest to analyse with this missionary family. The LMS’s response was too typical of an institution continually preoccupied with family issues while at the same time trying desperately to avoid them (and more particularly the financial outlay required for familial support). The role of the Crook children in the mission, meanwhile, it also eminently typical, with Mary and Hannah Jr. particularly involved in the teaching and women’s organisations that formed the staple of female missionary work. Hannah Crook (Sr.)’s life is also compelling, her extant diary (kept between 1819 and 1821) offering a fascinating glimpse into her life as a female missionary par excellence. Hannah taught, organised prayer meetings, and maintained a close relationship with the Island’s ‘Queen’ (to the extent of supervising the birth of Pomare III in 1820, and later taking over, with her husband, his education and upbringing).

Ultimately, the Crooks decision to leave the mission for the sake of their children was highly unusual, but their missionary life, in its extremes, highlights many more common features of missionary lives: a preoccupation with and continual anxiety about their children, a desire to replicate their vocation down the generations and to school their children in how to be missionaries, and a heartfelt belief that the LMS itself should take on some level of responsibility for their families. Missionary history has a troubled relationship with the idea of biography (due to generations of hagiographies clogging up the genre), but we cannot downplay the importance of the personal, the intimate and the emotional in mission history – it not only reminds us that historical actors and agents were three-dimensional people, wracked with many of the same anxieties and concerns as ourselves, but that as such their personal histories had a profound impact on the ‘public history’ of mission (if there even is such a thing).

– Emily Manktelow

References: Alex Calder, ‘The Temptations of William Pascoe Crook: an experience of cultural difference in the Marquesas, 1796-98’, Journal of Pacific History 31 (1996), pp. 144-61; Biographical Sketch of the Life and Labours of the late Rev. William Pascoe Crook, The Melbourne Argus, Friday 14 August 1846; correspondence from the LMS archive, South Seas Incoming Letters, held at the School of Oriental and African Studies.

Some erased Jamaican Colonial History, now revealed: My grandfather Herbert Theodore Thomas

1856 to 1930, was a white Jamaican Police Inspector, Lecturer, Naturalist, Explorer & the Author of 2 books; “Untrodden Jamaica”1890 & “The story of a West Indian Policeman”1927. His ancestors came to Jamaica as Moravian missionaries in 1754. He also lost his 4 sons who served in the British Army, as the first Jamaican Officers in WW-1. H.T. Thomas served the British Empire & Jamaica for 47 years and was awarded the King’s Police Medal in 1922. These step-uncles of mine are from my grandfather’s first marriage. I am the grandson from his 2nd marriage to my black Jamaican Grandmother Leonora Thomas, who gave him 4 daughters. To get the facts visit:

http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~jamwgw/ and scroll down to Links to Jamaican Genealogy. Thomas has become Jamaica’s forgotten man, for no reason but to deny the truth to the world. With my thanks. Gerald A. Archambeau -author.

Thanks, Emily, for such an interesting and informative article on the family life of my great, great, great grandparents.

I am a descendant of Hannah Crook. Thank you for your unique insights.

My late mother tried to research Hannah Dare a number of years ago but was never able to find anything on her, e.g. her date and place of birth, the Dare family tree, where she grew up, how she and William Pascoe Crook met etc. Would any readers of this site be able to provide me, and other readers of this site, with such details?

Hi Meredith

I too have been trying to find some information on Hannah. She must have been an amazing person. My research showed that she married William P Crook on 12 March 1803 at St Pul’s, Convent Garden. I have read the journal she kept for part of her time in Tahiti, but only have snippets of other information about her. I would like to find more about her life, both in Tahiti and in Sydney.

Steve

Wow, not sure how I missed this before. My aunt (Anne Twigg nee Langford)and I are also researching Hannah Dare’s story, and have made some progress. We are both related through Rebecca Crook, born in Tahiti in 1817, and are interested in the ‘women’s stories’. Would love to make contact with others that have an interest – this is a very exciting long term project! Annabelle.Leve@gmail.com

Lydia Crook is my Great, Great, Great Grand Mother. She married William Conway Armstrong. I have been researching the Crook family and while there is a lot of material available on William Pascoe Crook I haven’t been able to find much on Hannah or Lydia. I have read Hannah’s (Sr) journal which is held in the Mitchell Library, Sydney. Many of the entries in the journal are amazing. I cannot begin to understand how she managed to bring up a family and conduct her life in Tahiti. They could almost make a TV mini series on the Crook family!!! If anyone has information on Lydia, please contact me (stevea57@hotmail.com)